Their only son, Lawrence Stephen Basapa, was born the following year. In a recent interview, he said: “One of the first big words I learned was ‘workaholic’. Someone called dad that when I was maybe five. It wasn’t even in the dictionary at the time, but the meaning was explained to me, and it suited dad perfectly.”

T.A. Basapa worked long hours, with legal and other professional assistance, and with his brother, John Alexander (who had married a Muslim lady and adopted the Islamic faith; the couple had four children, all of whom migrated to Australia with their mother after his death in 1968).

The Basapa brothers’ work focused on re-documenting estate matters, clearing certain legal issues, collecting and banking rents, and establishing and maintaining even greater transparency in accounting and other functions.

Their step-siblings had made their own, separate ways in life. Aldewyn, who had married a Britisher, joined the teaching profession and worked his way to become principal of a top public school in Singapore. After his death, his widow and two children migrated. They now live in Australia and have changed their family name to Slade. Dorothy went to work in an administrative role in a major trading company. She too married a Britisher. The childless couple divorced after a few years and she never remarried.

Following his brother John’s death, T.A. Basapa worked relentlessly and with minimal assistance to keep the Estate of H. Somapah (decd) generating maximum income for its three beneficiary estates: the Estate of W.L.S. Basapa (decd), the Estate of Mynee (decd) and the Estate of G.V. Naidoo (decd) – each of which, in turn, distributes its one-third net income shares among its beneficiaries. (Trustees of the first of these beneficiary estates were Basapa and his step-mother Alberta Maddox, and Lawrence Stephen Basapa. Lawrence and his wife Celeste are now the trustees of this and Somapah’s estates.)

T.A. Basapa sold properties as they became inefficient and purchased newer properties that provided better returns, adhering to Singapore’s strict trust regulations – e.g. securing the approvals of Corpus and Income beneficiaries, and of the Court, before transactions.

But the workaholic always had time for his family. He was their pillar of strength.

“Dad put family above self,” said L.S. Basapa. “We all had the best he could afford, while he remained utterly frugal toward himself. Of course, the Estate and its beneficiaries were very much in his family, and dad saw his work as a duty to his family. He didn’t exactly get a ‘kick’ out of work as most workaholics do.”

However, through no fault of the trustees, the number of properties in the Estate dwindled – severely in the 1960s, less so in the years immediately after – although returns went on to improve considerably. These seemingly paradoxical developments resulted, respectively, from two factors: first, Singapore’s Land Acquisition Act, which was then structured to enable the authorities to acquire properties at prices favourable to themselves; and second, the abolition of the Rent Control Act.

Land acquisition saw the Estate of H. Somapah (decd) lose large numbers of houses, shop-houses and plots to the authorities for redevelopment and public housing projects. T.A. Basapa was furious, but even the best lawyers he engaged could not stop the powerful government machinery.

L.S. Basapa said, “In retrospect, I think dad should not have been stressed. In most cases, land acquisition turned out to be helpful. During Rent Control, we were getting pittance from each of those properties every month. And the Estate had to employ people to collect those miserable sums. Just imagine: most tenants were paying us just S$15-30 monthly, and subletting the premises for hundreds of dollars, and the law protected them. I think dad was sore really because those properties were his forebears’ legacy.”

With the money the Estate got from government for those properties, the trustees were later able to buy fewer properties, including luxurious ones, which paid better returns. And, when Rent Control was abolished, total income grew well above the levels when the Estate had a higher number of properties.

The smaller Estate of H. Somapah (decd) afforded T.A. Basapa time to build his own network and invest his own savings. He proved to be as astute as his forebears, although his investments were less adventurous. He entered the cyclical property market, prudently buying when prices were relatively low, and selling when they were on the upswing. He also invested in currencies and certain financial products.

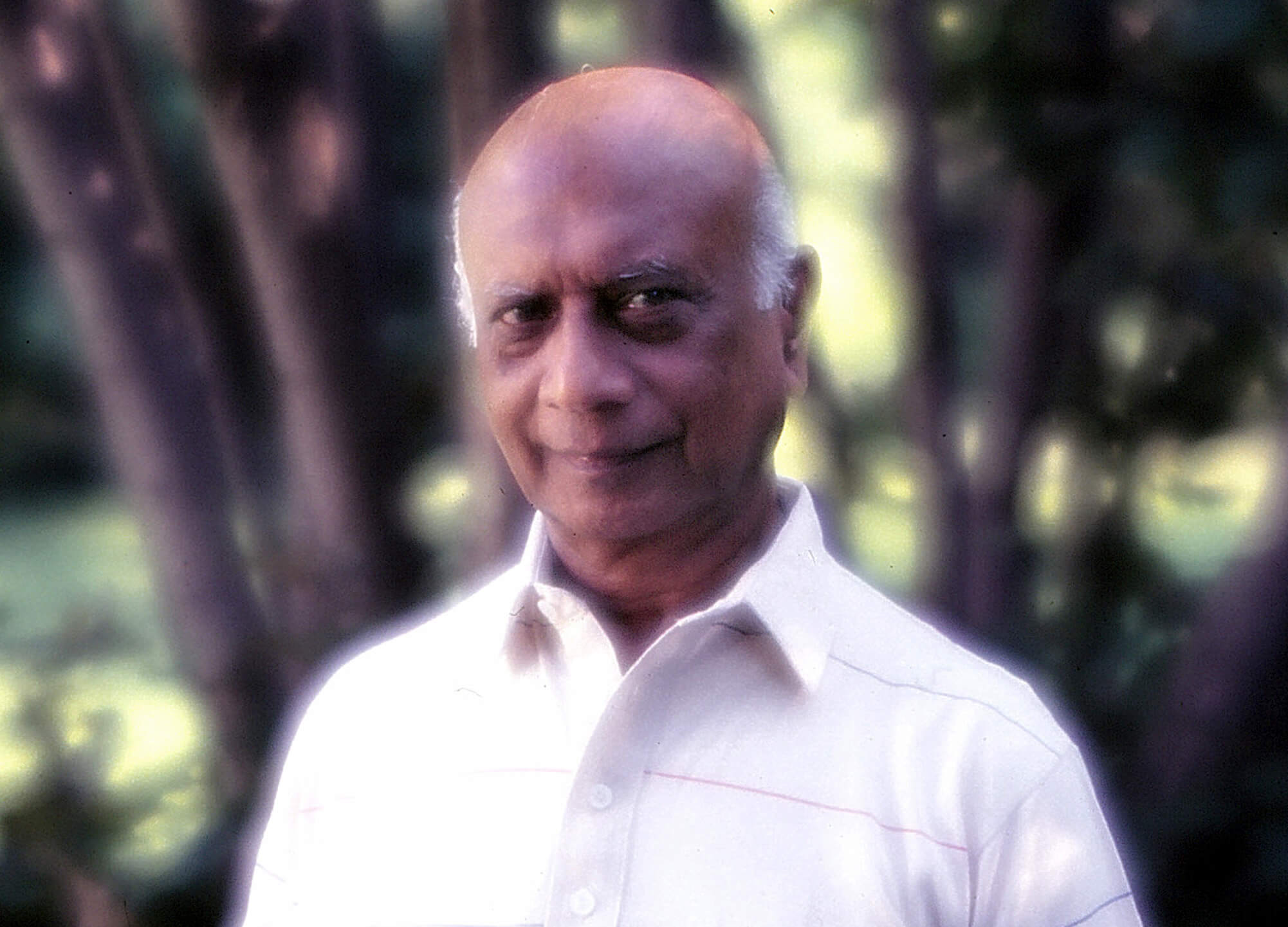

At the age of 50, T.A. Basapa was diagnosed with a heart condition. He battled the problem and kept working until he was in his late 80s, by which time he had suffered two heart attacks and his kidney function had begun to deteriorate. He soldiered on until his son, who had retired from his own career, and daughter-in-law, Celeste, took over the workload from him under his guidance.

“Dad left us peacefully, in his sleep, in the early afternoon of August 30, 2010,” said Celeste. “He’d been bedridden with pneumonia in his last weeks. He’d not gone visiting anyone in months. Days before he died, he told us that he didn’t expect too many people to attend his wake when it came, that he thought he’d been forgotten.”

He was wrong. The three-day wake drew several hundred who came to bid farewell to the quiet, family-oriented man they all remembered for his strength, dedication to his forebears’ legacy, and for his generosity.